The teacher must be content to proceed very slowly, securing the ground under her feet as she goes. Say––“Twinkle, twinkle, little star, / How I wonder what you are,” is the first lesson; just those two lines. (Charlotte Mason)

We start with more than two lines: three. The Mexican poet Tablada gave us a nature-study treasure of haikus.

- - - link / enlace to digital download (pdf) - - -

- - - link / enlace to physical purchase (Lulu) - - -

Un Día . . . y

Un Jarro de Flores

Juan José Tablada (1919, 1922)

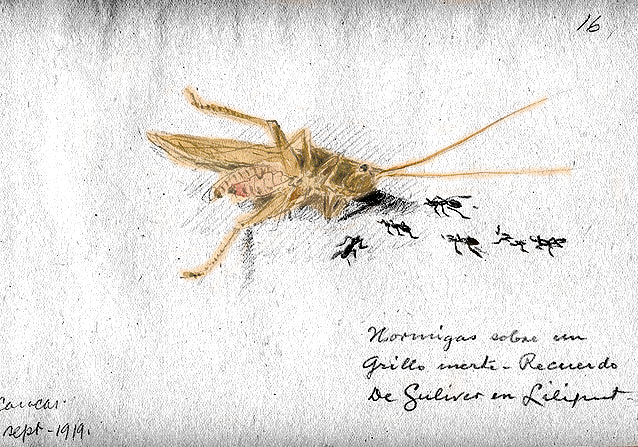

From childhood, Tablada lived getting close to animals, above all insects, which is an important factor to explain his closeness to the spirit of the haiku. The insects taught him that one does not have to judge based on size: there is a macro world in the micro. "The macro world within the micro world" is precisely the world of the haiki. (Ota)

This anthology includes two of his poemarios. These Spanish haikus include translations, but they are ready for beginning Spanish learners to delve into authentic, living poetry for memorization, recitation, and study.

editor’s introduction

I found a haiku by Juan José Tablada in an anthology for children. He was the first poet, and I was stunned. I never did finish that anthology and I started to read everything I could about Tablada.

I was educated in California, where a Spanish-speaking culture does exist, but not in a literary culture where poetry was frequently shared. Now, as a teacher, I’m always looking for texts to share with my students, and here, I found something perfect for my Spanish learners: brief poems – the breifests – about living, natural, and accessible things, but with a depth of theme, beauty, and fluidity.

Here is a collection of two books of haikus by Tablada, Un dia . . . (1919) y El jarro de flores (1922). I’ve only censored a pair of poems that are not appropriate for this collection. I have included original images from both poetry books.

My own translation to English is included. It is a literal translation. I wish to translate, word for word, so that the reader can quickly return to the original Spanish as quickly as possible. My translation does not attempt for beauty, but as a reference so that the reader can return to live the poem in its original language.

I have also included a few details of interest for the educator with an eyes towards nature, from a book by Ota.

editor José Francisco Moreno (2023) for academia late y llama

haikus written by Mexican poet on a nature study

One of my favorite things about Tablada is that he would fit in perfectly in a Charlotte Mason homeschool. As a young boy and throughout his adult life, he was observant.

The insects taught him that one does not have to judge based on size: there is a macro world in the micro. “The macro world within the micro world” is precisely the world of the haiku. Tablada mentions the depth of the micro world in “Hokku”, from El jarro de flores. About this, we will discuss in the chapter “The second collection of haikús “El jarro de flores”.

Tablada already loved the micro world due to his collecting of insects, but he had not noticed the cruelty that existed in collecting insects: that his entomological studies required the insects’ sacrifice. This became clear to him when he spoke to the monk of a temple in Honmoku during his visit to Japan; when he was about to kill a serpent that quickly crossed his path in the temple garden, the monk stopped him, yelling, and told him: “If men cannot give life, at the very least we should not destroy it [ . . . ]”. But what great reminder of that spiritual lesson?, said Tablada. He would unconsciously feel that Buddhist way of capturing the soul within the life all beings. (Seiko Ota in "Interest in Insects")

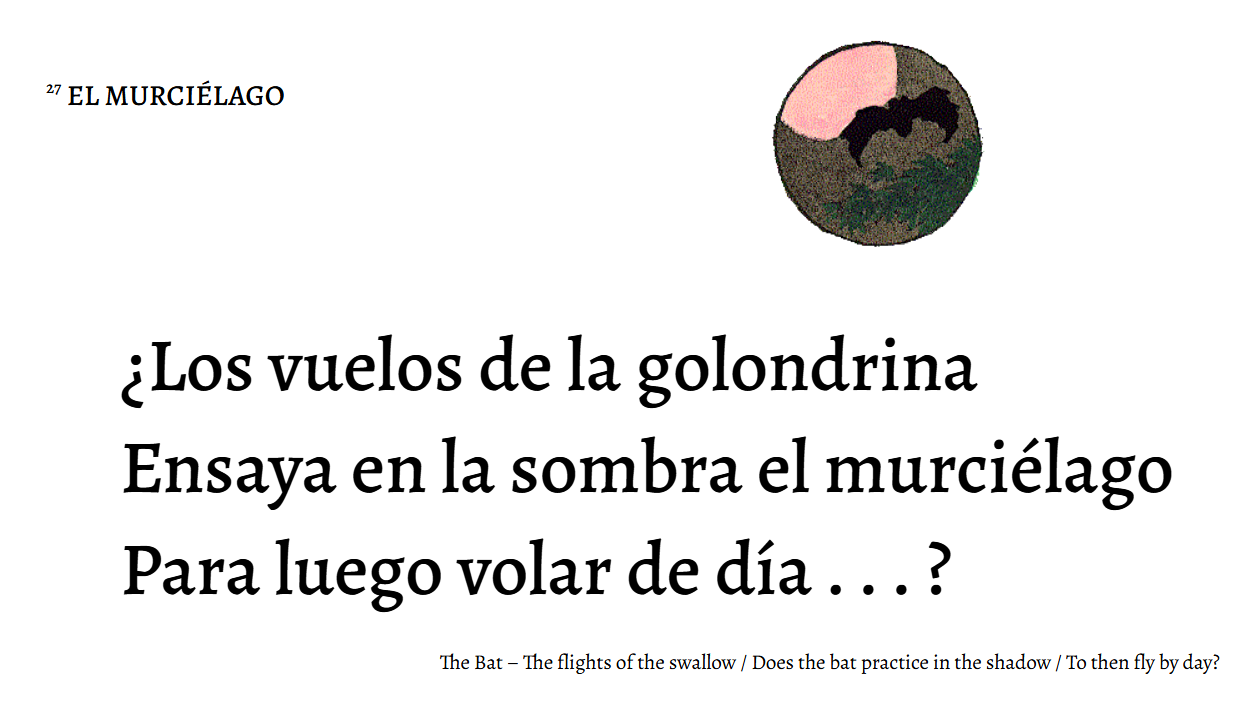

Tablada wrote about BATS.

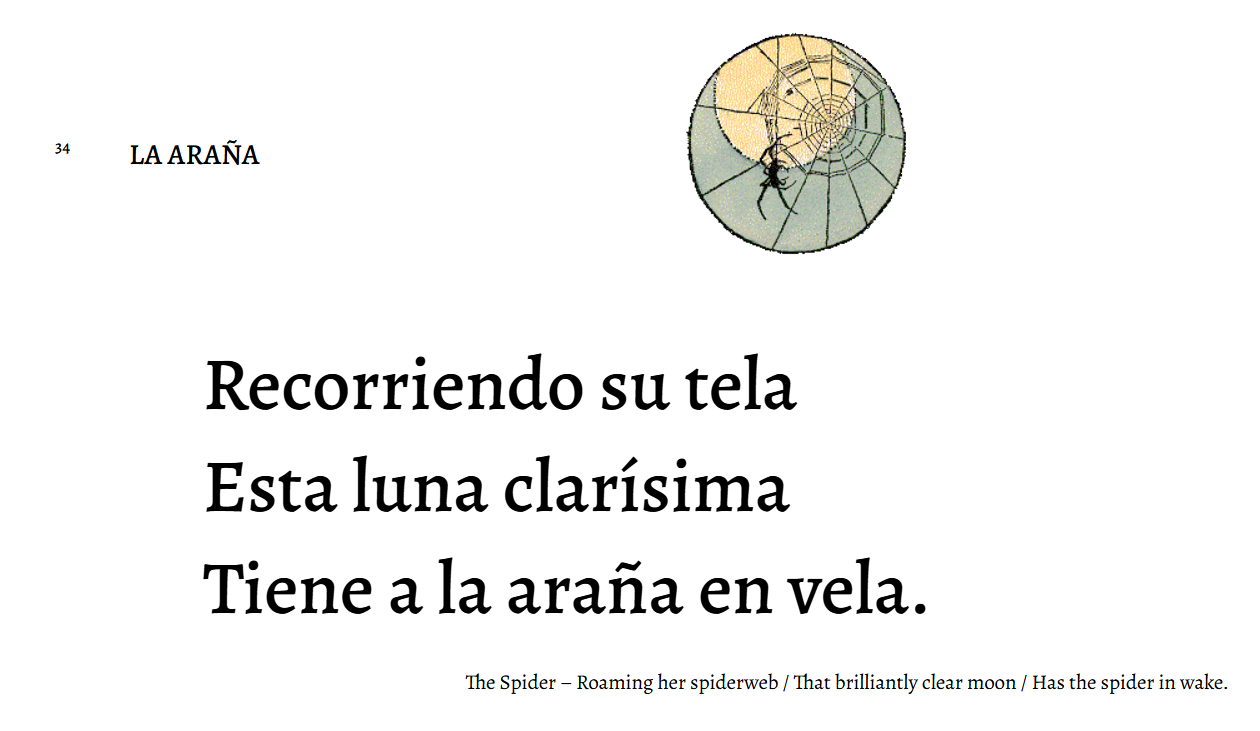

Tablada wrote about SPIDERS.

Tablada wrote about FIREFLIES.

Tablada wrote about TOADS.

One of the most fascinating things about his first book of haikus is that Tablada illustrated each poem. In our anthology, these are reproduced to bring Tablada's words to life.

Tablada introduced the haiku to the Spanish-speaking world

Tablada's second poemario also had short poems, that continued to be snapshots of natural life. He expanded into other topics and while he didn't illustrate this edition, there's a whole lot to be said about the artist he hired to fill some of the pages with artwork. We have supplemented the poemario with illustrations from other words from the same author.

Todos los días hacíamos excursiones a pueblecillos cercanos [ . . . ] que despertaban en mi esposo recuerdos infantiles, los de un viaje con su madre a Mazatlán, cuando él tenía tres o cuatro años apenas; [ . . . ]

También me decía que en todos aquellos hermosos lugares de Colombia, la naturaleza, la perspectiva de los montes, los apretados bosques, los rumorosos macizos de bambúes, le recordaban poderosamente al Japón.

so many recordings in the Moodle

These Tablada poems are the first poetry recitations that we ask our students to practice. We try to align to practices that families already engage in, for example morning recitations or poetry tea-time or copy work. Our students find these poems the perfect length to start, the perfect topic to engage their curiosity, and most of all, a kindred spirit in a poet who noticed the very smallest insects and bugs.

Oh, and we almost forgot to mention that each poem has an original translation into English! Other things our students find in our Moodle courses are:

- Hear It: Enjoy carefully curated audio recordings of Tablada’s Poemarios to engage with the rhythm and beauty of the texts.

- Read It: Access the full poems with accompanying resources to explore their meaning and structure.

- See It: Discover visual materials that complement the poems and bring the themes to life.

- Practice It: Expand your learning with exercises and activities designed to deepen your understanding and appreciation of Tablada's work.

Our goal is to provide a meaningful and immersive way to explore early resources, with Tablada’s Haikus as a centerpiece of language and literary discovery.